Living In Color: playful, vulnerable, connected

Kylie Marsh

2nd April 2024

When you hear about an art show that exhibits work with the theme of being a person of color in the South, what do you picture?

The Raleigh Film & Art Festival, a multi-disciplinary festival, is one of the largest independent and student film festivals in the Southeastern region. It aims to connect independent artists to new audiences.

Background

The festival was founded in 2012 by visual artist Christopher Terrell. While the eponymous event is held every October, its Living in Color art show takes place the entire month of February.

“Last year, we had maybe 15 artists of color whose art you may never see in any other place,” Terrell said. “We work with the HBCUs, high schools, and we even had middle schoolers. And we were able to put them together with seasoned artists that they can learn from.”

Terrell says the organization seeks to celebrate artists of color; being the founder, an artist of color himself.

“I was born in South Raleigh around a lot of the trials and tribulations that are conditions of a lot of the south side of a lot of cities. Drugs, death, all those things in a single-parent home with a very loving mother,” he said. “Overcoming those things and not allowing the conditions that were around me to condition me, that’s a part of the platform of what’s been created with the Raleigh Film and Arts Festival.”

The show took place at the Greg Poole, Jr. All Faith Chapel at Dorothea Dix Park, a historically significant site for several cultures and communities and an International Site of Conscience.

“We give an opportunity for every stage of development but also like to mix those people in those different stages of development with others who can also pour into them and share,” Terrell said.

The Show

The Dix Park website says the chapel features “mid-century modern architecture…with decorative wood elements, a rose stained-glass window, terrazzo floors, and mid-century stainless fixtures.” That said, though it was a bright, sunny day outside, the fluorescent lights inside and slits for windows did not illuminate the gallery floor enough to do the pieces justice. When not furnished with pews or chairs, the size of the space is immense; works were displayed on the brick-paneled walls to the right and left of the stage. Some of the pieces were slightly hung crooked.

Labels for pieces didn’t have detailed descriptions about the work or the artists; just a QR code that linked to a page to inquire about purchasing the pieces. This choice points toward a not-so-subtle contradiction: artists of color need to eat, and they often struggle to get the platforms they need to either express themselves authentically or make a living. This means they usually have to choose between one or the other.

The Works

One of the first pieces you would have seen upon entering the chapel were three glossy black-and-white photos of a young Black girl giggling and playing. She is too young to yet be worried about the opinions of others. She is too young to worry or consider the way others may perceive her because of the color of her skin, or her gender.

Micheal Shaw is a professional photographer from Rochester, New York who relocated to Raleigh about five years ago with his wife and daughter. The photos depict Shaw’s daughter, Jenisis, after being diagnosed with stage four kidney cancer.

“These photos are almost a documentary of her journey,” Shaw said. One photo, in the middle, features Jenisis sitting in her mother’s lap. Her mother’s back is turned to the camera, and the young girl’s head is thrown back in laughter.

“She was always kind of chipper, but at the time, I was assuming she didn’t really know the severity of what was going on,” Shaw said. “As she’s gotten older, she told me it wasn’t that she didn’t understand, it was just the way that she chose to face it.”

The photos were originally shot in color, but Shaw chose to change them to black-and-white later on.

“Ironically, it was ‘living in color,’ but my interpretation was through the lens of Black and white,” he said. “It’s almost like when you turn the volume off. You turn the volume and you get the raw content of just what the pictures are. You don’t get the hues and colors.” Shaw explained that subjects’ body language, gestures and facial expressions communicate more through the photo in black and white than colors would.

Shaw’s non-profit for his daughter, Team Jenny Bean, has an initiative called Portraits with a Purpose which gives complimentary photo sessions to families with children facing terminal illnesses.

“People ask, ‘why would you want that?’” Shaw explains, referring to the photos that remind people of some of their most painful times. “But there’s a raw innocence and purity to the love and expression when a parent and child are going through something that threatens them.”

Roxanne Yvonne, another Raleigh-based photographer, met Shaw at the show’s opening. They bonded over a similar experience with illness: Yvonne was recently diagnosed with lupus nephritis. Some of her other works take a documentary-style focus.

One of these, displayed on the other end of the room, is called “The Boyz.” The snap is from 2017, taken in downtown Raleigh when Yvonne’s two best friends wanted her to take photos for their rap group. The image depicts two Black men, perched dangerously hanging from the railing above a giant gap. They gaze down at lights coming from below, which extends beyond the frame. A soft focus gives the image intensity.

This image follows a similar theme to Shaw’s images: it depicts Black joy. The photo’s subjects are two friends fooling around downtown. The soft focus makes the viewer feel like they’re along for the adventure.

“’The Boyz’ is just…boys being boys,” she says with a laugh.

Yvonne started photography after realizing she preferred to be behind the camera than in front of it. To her, Living in Color was a show with flexible parameters; and she’s grateful because it was her first time being in a show like it. She got the opportunity to meet fellow artists and received great feedback.

Though Yvonne loves doing portraits, she hopes to do more artistic work in the future, especially with photo editing. She’s still relatively new to the art world.

“It’s very scary. All eyes feel like they’re on you, and then people seek you out to get your opinions” she said. “Being displayed in something like this was very big, but also very small, and it was the first step into the art world.”

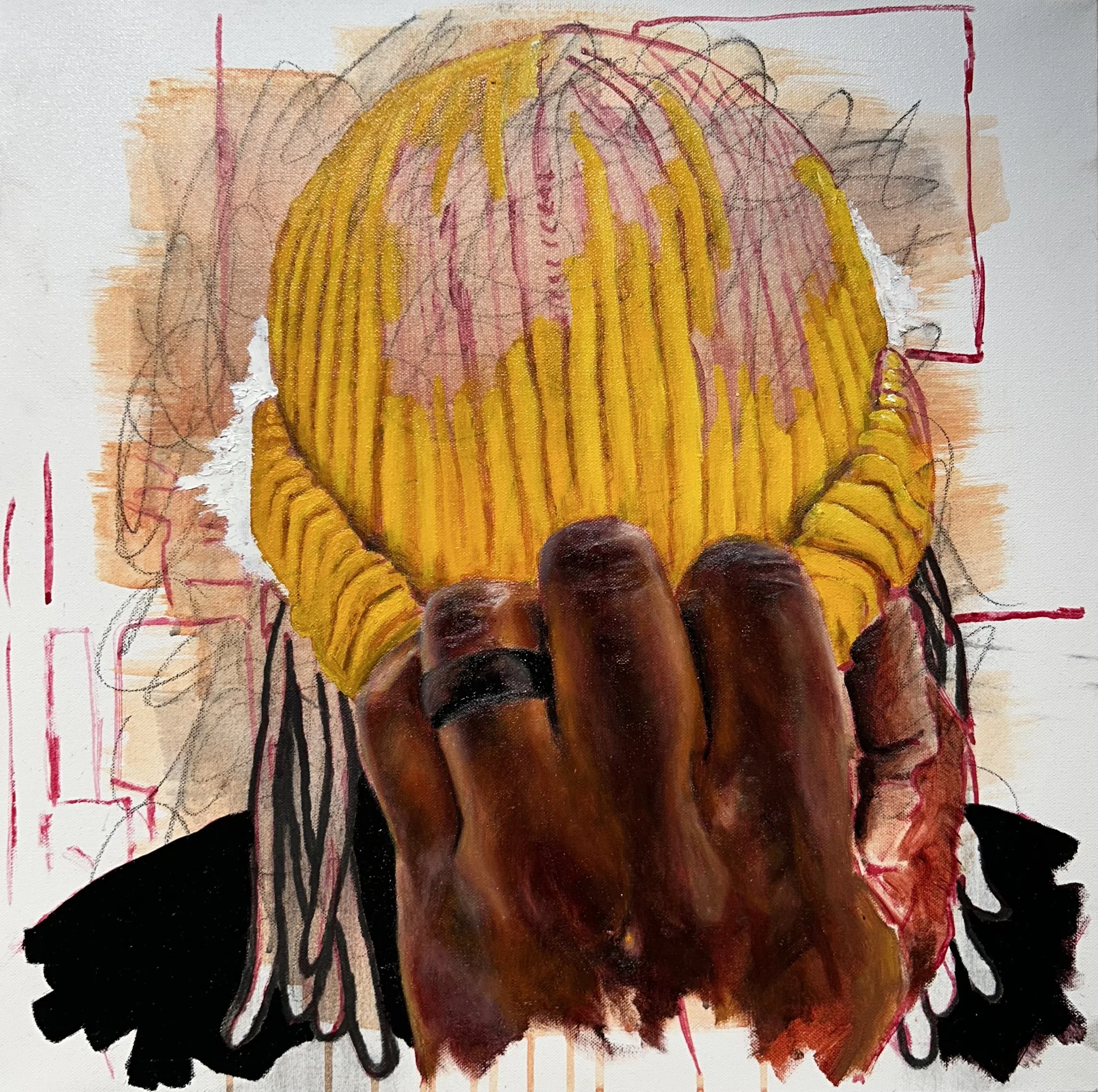

Further into the chapel, a series of self-portraits by art therapist Lamar Whidbee show the artist looking at the viewer through tired, confused eyes, before shrinking to hide his face under his yellow beanie.

Whidbee was born and raised in Hertford, North Carolina and went to college at NC Central University on a football scholarship. Duke University Professor Beverly McIver encouraged him to seriously pursue art instead of football. He got an MFA at UNCC and his license for clinical mental health counseling at NC State University.

He pursued art seriously at McIver’s direction and turned it into an occupation.

“To see her consistently do shows and make work, that was her job, to be creative, she was the model, and in a lot of ways, she still is.”

Whidbee says he’d describe himself as an emerging artist over an established one.

“I have a standard for myself, and I haven’t reached that yet,” he said. He imagines an established artist has routine and consistency, something he’s still learning to do and experimenting with.

Whidbee’s most recent show is called “Amygdala,” after the part of the brain responsible for our fight-or-flight response. The paintings are an exploration of his own gut reactions and behavior in the world, specifically as a husband and father.

“Why do I behave a certain way, and why do I see the world and certain people in a certain way?”

The self-portraits are called, “As a man,” and depict an exploration of his own emotions. Some of the painting fades out of full-color into just outlines of his figure. The background has pencil scribbles, meant to channel the art of calligraphy.

“A lot of men, whether clients, myself or people; men have a hard time communicating. Why?” Whidbee asks. “It’s questioning what masculinity is, and what it means to be a man.”

The portrait doesn’t show too much emotion. The man is tired. His eyes seem to show pain, and yet his expression is stoically blank. Though his head isn’t fully in both hands, his hand still offers self-soothing. There’s something on this man’s mind.

Though these portraits don’t touch on race, their position in the show brings the issues and emotional stigma that Black men face further to the surface.

“I never mention being Black,” Whidbee says. “So let’s think about that part. If I’m dealing with all of these emotions, and talking about family and raising my children and all that and I never even mention being Black…how much more am I dealing with?”